1 – Resigning from 21st century workplaces

There’s nothing we do with as much regularity, intensity and unquestioned submission as work.

—

Jamie McCallum

The Tyranny of Work

Late in 2021, nearly two years into a worldwide pandemic that reshaped everything about how and where people did their work, the workforce in countries around the world underwent ‘The Great Resignation’. People started leaving their jobs in droves, often without a new job to go to, and all at a time when most aspects of daily life were affected by peace-time-high levels of uncertainty.

Country-wide lockdowns served to highlight marked inequalities of workers conditions. Many office-based employees experienced two years of unprecedented flexibility with the hours and modes of working. Yet workers remained disillusioned with their jobs – to the point that they handed in their notice. Clearly the issue is not how and where we work; it’s why and what we do for work.

Work doesn’t often get the best out of us. It can be low on purpose, impact and passion. It restricts freedom and empowerment. Dynamic, performant teams are hard to come by – as are chances to experiment in different roles and industries.

Work also comes with long-term, large-scale issues, such as fair access and fair pay for all. The opportunities for growth and taking on responsibility are regimented, often lacking flexibility and personal fit. The modern workforce is significantly less tolerant of these shortcomings than preceding generations, searching for new problems, roles, and industries with a greater frequency than ever before.

Unfortunately, opportunities to work for (or to create) high impact organisations are rare, as are opportunities to define one’s own role, to organise ourselves, and to work on projects of interest.

Because of the dominance of the ‘free’ market, the liberal market economies of the UK, US and Australia typically result in short-term and discordant relations between employers and employees. The power dynamics and incentives of work are aligned with returns to the shareholder, not returns to the workforce, the community, and the environment. These imbalances between motivation and remuneration are as unsatisfactory as they are unsustainable. We need to find another way.

2 – Nirvana, Valhalla, etc.

There are two ways of looking at the work you do to earn a living. One is the way proposed by the late Henry Ford. Work is a necessary evil, but modern technology will reduce it to a minimum. Your life is your leisure lived in your free time. The other is to make your work interesting and rewarding. You enjoy both your work and your leisure. We opt uncompromisingly for the second.

—

Ove Arup, interviewed in 1970

More satisfactory work would encompass three main traits:

- The output of one’s role would add value to both the planet and its inhabitants; the work would provide purpose and satisfaction.

- The freedom and variety to easily join, contribute and leave projects; while working in passionate, high performing teams.

- One’s work would be fairly rewarded.

Within this utopian vision of work, deciding what to work on quickly becomes the key question to answer. Fortunately, the UN has already provided an excellent cheatsheet of valuable areas of focus: the UN Sustainable Development Goals – a collection of 17 goals that interlink to form “a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all people and the world by 2030”.

The goals are inspirational and Herculean, including the eradication of poverty, hunger, and gender inequality; providing a quality education to everyone; taking action towards the climate emergency; and improving the conditions of life both on land and in the ocean. Progress towards the goals is monitored by 232 indicators. Working on just one of the indicators would provide definable purpose; achieving one leaves the world quantifiably better than before.

It’s clear that the world has no shortage of options when it comes to working on things that matter. With the question of what to work on answered emphatically, we can turn our attention to figuring out how best to contribute. This is why we started Otio.

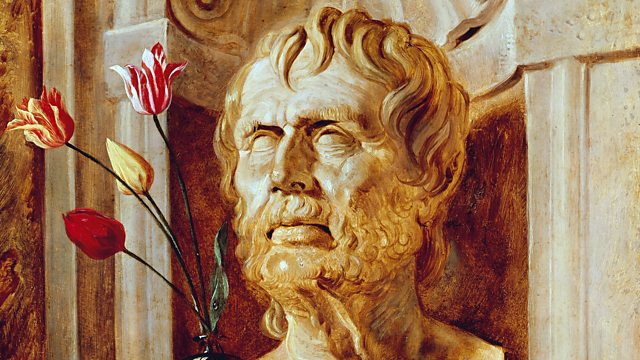

3 – De Otio

This of course is required of a human; to benefit their fellow humans.

—

Seneca the Younger

At its core, the Otio Collective is a community of effective, like-minded people exploring ways to redefine ‘work’ – a digital talent pool centred around a desire to work on more purposeful initiatives.

We’re remote and distributed. For now, we’re part-time and voluntary, but our vision is for Otio members to work on projects that generate them a fair wage.

We work on things that make a positive difference to the world, and as such we’re committed to contributing to the UN SDGs. As project ideas and opportunities arise, we experiment with new ways to collaborate and problem-solve. Self-organising teams of Otio members form to work on specific projects. As the projects gain momentum, the teams grow and evolve to stay efficient and effective. Sometimes, the nature of a project means that a new organisation is formed, and spun out of the community.

Otio project teams are self-organising. There is no traditional leadership structure or hierarchy, but crucially this doesn't mean that there aren't clearly defined roles within projects. The difference comes in how those roles are appointed: We frequently rearrange ourselves, experimenting with different voting mechanisms such as lottocracy and quadratic voting to ensure democracy and self-governance. This also helps us maintain flexibility with how, when, and where our members contribute to the projects they work on.

Our vision is two-fold: to work on better things, and to work on things better. If this sounds like something you’d like to contribute to, the first step is to join the Slack group and introduce yourself. We need proposals for new projects, and support for existing ones. We need help to grow and engage the community. We need diversity of approaches, interests, backgrounds, experience, and skill sets.

In the words of Indy Johar, “The biggest revolution of the 21st century will not be our technology, but how we organise ourselves”.